|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 17 2024, 12:15am

Post #1 of 68

(12215 views)

Shortcut

|

|

***Shire Discussion: General Hobbit Culture

|

Can't Post

|

|

Welcome to the Shire Discussion, and thanks to Ethel for organizing us!

Radagast to Gandalf: "All I knew was that you might be found in a wild region with the uncouth name of Shire.”

What are we to make of this uncouth land which is hiding a trifle that Sauron fancies?

THE LAND

First off, there seems a special connection between the land of the Shire and the Shire-folk that is reminiscent of the Elf-environment connection made more explicit elsewhere.

When the Fellowship is in Hollin, Gandalf observes: 'There is a wholesome air about Hollin. Much evil must befall a country before it wholly forgets the Elves, if once they dwelt there.’

‘That is true,’ said Legolas. ‘But the Elves of this land were of a race strange to us of the silvan folk, and the trees and the grass do not now remember them. Only I hear the stones lament them: deep they delved us, fair they wrought us, high they builded us;...'

I firmly believe that if the hobbits left the Shire, an Elf would hear the fields and woods lament them: "deep they tilled us; carefully they tended us; merrily they laughed and drank upon us."

And it seemed that the rich, gentle land of the Shire shaped the hobbits as much as they shaped it:

The land was rich and kindly, and though it had long been deserted when they entered it, it had before been well tilled, and there the king had once had many farms, cornlands, vineyards, and woods.

Could the hobbits have evolved their culture anywhere else in Middle-earth? Could we expect a similar Shire in Harad or Rhun, or in the middle of Gondor? Or did it lie at a unique wilderness juncture of protection by Elves, Rangers, and a Grey Wizard, enabling its people to prosper and indulge in pleasant pastimes? (While the Dwarves were frequent in the Shire, I don't see them playing a protective role.)

THE PEOPLE

While Tolkien mentions a few things hobbits don't like such as complex machinery, by and large he develops their culture by demonstrating what they enjoy.

they love peace and quiet and good tilled earth: a well-ordered and well-farmed countryside was their favourite haunt.

Not that it ends there. Birthdays were a perpetual delight.

Actually in Hobbiton and Bywater every day in the year was somebody’s birthday, so that every hobbit in those parts had a fair chance of at least one present at least once a week. But they never got tired of them.

And drinking and eating from noon to midnight was easily achievable regardless of age.

At other times there were merely lots of people eating and drinking – continuously from elevenses until six-thirty, when the fireworks started...About midnight carriages came for the important folk.

Does this sound like Rivendell or Minas Tirith to you? Can you readily imagine all-day community birthday parties and fireworks in those places? (rhetorical) What does it tell us about hobbit priorities in life?

Mixed in with conviviality is the hobbit penchant for gossip, either in taverns or in homes like Farmer Maggot's:

‘Drownded?’ said several voices. They had heard this and other darker rumours before, of course; but hobbits have a passion for family history, and they were ready to hear it again.

Though curiously hobbits' love of gossip-history doesn't connect with a love of lore-history.

A love of learning (other than genealogical lore) was far from general among them,

Do hobbits make sense in a Middle-earth where history is usually revered by the wise and ignored by the foolish? What could explain hobbits' disinterest in history?

Next up I would point out how hobbits possess an innate sense of humor and a general prankster nature:

Practically everybody living near was invited. A very few were overlooked by accident, but as they turned up all the same, that did not matter.

He gave away presents to all and sundry – the latter were those who went out again by a back way and came in again by the gate.

Along with Bilbo's parting gift memos, which often included a joke of some kind, and only Lobelia was reported to be offended.

After Bilbo's party, there was chaos at Bag End as young hobbits knocked holes in the cellar walls looking for treasure and

A false rumour that the whole household was being distributed free spread like wildfire; and before long the place was packed with people who had no business there, but could not be kept out. Labels got torn off and mixed, and quarrels broke out. Some people tried to do swaps and deals in the hall; and others tried to make off with minor items not addressed to them, or with anything that seemed unwanted or unwatched.

Frodo remains curiously unruffled: while there are virtually no police to call (only 12 Shirriffs total), he doesn't employ security guards or fieldhands or anyone else to restore order by force or violence. To me this seems like part of the acceptable prankster culture in the Shire and thus no cause for alarm.

Birthdays, parties, drinking, eating, gossiping, pranks: is this the uncouth land of Shire people who are lazy and lower class? Or is there something beyond class that comes to mind?

For me, hobbit culture is best summarized as some mix of childhood and adolescence, where all these things are the obvious priorities in life, and other things like "career ambitions" lie in the realm of Boring Grownups. I'll add one more observation about Things That Boring Grownups Would Think Up when Bilbo's will is described:

It was, unfortunately, very clear and correct (according to the legal customs of hobbits, which demand among other things seven signatures of witnesses in red ink).

Does hobbit culture appeal to you? Is the Shire a great place to live, or just a nice place to visit? Are hobbits an ideal that readers should aspire to, or should we be more like Elves (serious and contemplative), or should we try to be both? Or should we be Riders or Rohan or Faramir or Aragorn--darn it, who should I be emulating in this trilogy?!?!

Why does Shire culture produce quest heroes like Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin? If Shire culture is so happy and successful, why isn't it emulated by the other peoples of Middle-earth? If you were going to change anything about the Shire (which sounds blasphemous, so tread lightly, my friends), what would it be?

What else should we be discussing when we bring up general hobbit culture? And thanks for reading and participating! (apologies for the varied formatting)

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 17 2024, 1:28am

Post #2 of 68

(12099 views)

Shortcut

|

the land makes the people to some extent. It certainly is symbiotic at the least.

And I've always loved the idea in Tolkien that the land, trees, and stones can speak--and even remember.

This is really nice: "deep they tilled us; carefully they tended us; merrily they laughed and drank upon us."

|

|

|

Curious

Gondolin

Apr 17 2024, 3:04am

Post #3 of 68

(12096 views)

Shortcut

|

Q. Could the hobbits have evolved their culture anywhere else in Middle-earth? Could we expect a similar Shire in Harad or Rhun, or in the middle of Gondor? Or did it lie at a unique wilderness juncture of protection by Elves, Rangers, and a Grey Wizard, enabling its people to prosper and indulge in pleasant pastimes?

A. The Shire as Tolkien describes it is in fact based on the rural English village of his childhood. It's full of anachronisms that don't fit with the rest of Middle Earth. Tolkien acknowledges this in the Appendices, where he blames the anachronisms on his extremely loose translation of the original. Even the names of the hobbits are completely different.

So it's hard to say what the culture of the hobbits in the Shire really is, or really would be if Tolkien had made any effort at plausibility. That said, we do know that Golllum and Bilbo had common ground even though their respective cultures had been separated for hundreds of years. There was at least one other settlement of hobbits in Middle Earth, and they had some things in common with the hobbits of the Shire.

We also know that the Drúedain, the Wild Men who lived in Drúadan Forest north of the White Mountains, had a completely different culture even though they lived near Rohan and Gondor. There seem to be pockets of people all over Middle Earth who keep to themselves as much as possible and don't know much about even close neighbors, let along distant peoples. Gandalf and Aragorn may be the only inhabitants of Middle Earth who travel enough to know most of these insular communities.

So yes, I think the hobbits might have found another fertile and relatively isolated land to settle somewhere. They just needed some fertile land to till, and they would make it their own.

Q. Does this sound like Rivendell or Minas Tirith to you? Can you readily imagine all-day community birthday parties and fireworks in those places? (rhetorical) What does it tell us about hobbit priorities in life?

A. In The Hobbit the elves of Rivendell seemed quite light-hearted and full of child-like humor. They particularly enjoy teasing the visiting dwarves. In LotR they seem more somber, but it's a more somber time.

That said, the Shire is different from Rivendell or Minas Tirith. Elves and Men and Hobbits all have different interests. And while the Shire may seem idyllic, the hobbits themselves can be petty, gossipy, and irritating. Note that Bilbo has no close friends his own age. He must make do with Frodo and Frodo's friends.

Eating, drinking, and birthday presents were a daily event in the Shire, but not fireworks. That was a Gandalf specialty.

And the usual birthday presents were nothing like the ones Bilbo gave away. If you are giving multiple gifts almost every day of the year, you have to keep within budget. I'm sure there was a lot of regifting, too, and many hobbits might find themselves receiving a gift they had given away a month or year before, as it made the rounds.

As for hobbit priorities, Thorin said it best:

“If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

The Shire is not a utopia, but it's pretty nice, nonetheless.

Q. Do hobbits make sense in a Middle-earth where history is usually revered by the wise and ignored by the foolish? What could explain hobbits' disinterest in history?

A. As I said, the hobbits and the Shire are anachronistic. They are modern, and therefore uninterested in history. The rest of Middle Earth is more akin to ancient cultures, where history -- at least of kings and generals and heroes and heroines -- was revered.

Q. Birthdays, parties, drinking, eating, gossiping, pranks: is this the uncouth land of Shire people who are lazy and lower class? Or is there something beyond class that comes to mind?

A. Radagast does not call the land of the Shire uncouth. Indeed, he knows nothing about it. He calls the name "Shire" uncouth, presumably because it doesn't roll off his tongue. But what sounds strange and uncouth to Radagast may not sound that way to Gandalf. Radagast, despite being one of the Istari or Wizards, is provincial. He stays among the beasts and rarely visits anyone else.

Q. Does hobbit culture appeal to you? Is the Shire a great place to live, or just a nice place to visit? Are hobbits an ideal that readers should aspire to, or should we be more like Elves (serious and contemplative), or should we try to be both? Or should we be Riders or Rohan or Faramir or Aragorn--darn it, who should I be emulating in this trilogy?!?!

A. The Shire is not a utopia but it is peaceful and fruitful, at least before Saruman gets involved. But the hobbits themselves can be quite irritating, wrong, ignorant, and stubborn. They are also quite conservative and set in their ways. In short, they have the virtues and vices of English villagers in the late 19th century. But at least they don't murder each other, and that's better than many other cultures of Middle Earth.

Q. Why does Shire culture produce quest heroes like Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin?

A. It normally doesn't. These are exceptional hobbits. And they are the direct result of Gandalf's meddling. He deliberately infected Bilbo with the wandering bug, and interest in elvish, and all kinds of strange notions and knowledge, and it just took a while for it to spread to another generation of young hobbits.

Q. If Shire culture is so happy and successful, why isn't it emulated by the other peoples of Middle-earth?

A. As I said, it's not all good. They are also ignorant and petty.

Q. If you were going to change anything about the Shire (which sounds blasphemous, so tread lightly, my friends), what would it be?

A. I would give Bilbo and Frodo more friends.

Q. What else should we be discussing when we bring up general hobbit culture?

A. Maybe the fact that Tolkien, despite his learning, believed he had much in common with the hobbits:

"I am in fact a Hobbit in all but size. I like gardens, trees, and unmechanized farmlands; I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking; I like, and even dare to wear in these dull days, ornamental waistcoats. I am fond of mushrooms (out of a field); have a very simple sense of humour (which even my appreciative critics find tiresome); I go to bed late and get up late (when possible). I do not travel much."

Letter 213. I suppose Tolkien was something like Bilbo, odd in some ways but still a hobbit with mostly hobbit tastes.

(This post was edited by Curious on Apr 17 2024, 3:08am)

|

|

|

Silvered-glass

Nargothrond

Apr 17 2024, 11:56am

Post #4 of 68

(12046 views)

Shortcut

|

Could the hobbits have evolved their culture anywhere else in Middle-earth? Could we expect a similar Shire in Harad or Rhun, or in the middle of Gondor? Or did it lie at a unique wilderness juncture of protection by Elves, Rangers, and a Grey Wizard, enabling its people to prosper and indulge in pleasant pastimes?

I think the hobbits would have produced something similar to the Shire as long as they had a) fertile farmland and suitable weather, and b) absence of outsiders seeing the prosperity and deciding to invade. The second point is the difficult one in a troubled place such as Middle-earth.

Does this sound like Rivendell or Minas Tirith to you? Can you readily imagine all-day community birthday parties and fireworks in those places? (rhetorical) What does it tell us about hobbit priorities in life?

I think the priorities of life in Rivendell are not fundamentally so different from those of the Shire, but the population of Rivendell being immortal would naturally give a different perspective.

Minas Tirith is a different place entirely, shaped by the threat of Mordor and the need for strong central government.

Do hobbits make sense in a Middle-earth where history is usually revered by the wise and ignored by the foolish? What could explain hobbits' disinterest in history?

The book quote using the words "far from general" implies in its negation that a significant number of hobbits, perhaps even the majority, did have a love of learning. Of the main cast, Bilbo, Frodo, and Merry are downright scholars, and Sam also has an interest in learning about various things. Pippin is the least interested character, but it is unknown whether this might change with maturity. That's 80% love of learning in this admittedly non-random sample.

Birthdays, parties, drinking, eating, gossiping, pranks: is this the uncouth land of Shire people who are lazy and lower class? Or is there something beyond class that comes to mind?

The Shire doesn't have a culture of snobbery even among the high class. I can see this starting to change after the ending of the book with hobbits seeing the Gondorian culture as superior and worth emulating, though Aragorn's decree of banning humans from the Shire could get in the way of this.

Does hobbit culture appeal to you? Is the Shire a great place to live, or just a nice place to visit? Are hobbits an ideal that readers should aspire to, or should we be more like Elves (serious and contemplative), or should we try to be both? Or should we be Riders or Rohan or Faramir or Aragorn--darn it, who should I be emulating in this trilogy?!?!

The hobbits are meant to be ordinary people and familiar in many ways to the original intended audience. This has been obscured by the passage of time in the real world. Because of this the Shire wouldn't feel as cozy and familiar to me as it would have to people of Tolkien's time.

I think Tolkien's character development is deeper than most people give him credit for, so I don't see the likes of Faramir or Aragorn as meant to represent flawless ideal heroes. I think Tolkien didn't write characters with the intention of having them emulated by the readers. The most "perfect" hero in Tolkien might be Gil-galad and that's because he really has no detectable personality because of the narrative distance and the limited amount of knowledge we have of him. Gil-galad also dies heroically before he gets to do something to ruin his reputation, such as trying to take the One Ring for himself.

Why does Shire culture produce quest heroes like Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin?

I think the key point in this is that a secure and happy early childhood has in each of these characters produced a strong belief in the fundamental goodness of the world that allows for them to keep going, even when the situation seems hopeless and the power of the Dark Lord seems overwhelming. Even Frodo benefits from this despite the early death of his parents. He is the least optimistic hobbit already in the beginning of the story, though.

If Shire culture is so happy and successful, why isn't it emulated by the other peoples of Middle-earth?

Eriador is a post-post-apocalyptic setting, so many peoples simply would have no idea about the Shire even existing. Then there is the issue of different cultures having different values. Dwarves for example aren't going to become farmers just because they see hobbits being happy as farmers. Many countries also have real practical need for standing armies, etc.

If you were going to change anything about the Shire (which sounds blasphemous, so tread lightly, my friends), what would it be?

The Shire is dynamic, not static, and will change on its own, both from internal and external reasons. The Shire as depicted in the books is not in balance with nature and will continue to expand its borders as long as the birth rates remain high and no external force, such as running out of places to expand or a conflict with a more martial culture, gets in the way.

The happy Shire in the books is an accident(?) in time that contains the seeds of its own destruction - or at least radical change for better or worse.

What else should we be discussing when we bring up general hobbit culture?

- Cultural and technological development in the Shire. The hobbits as scientists, engineers, and capitalists. Foreign trade and relationships with other cultures.

- The hobbits as fairy creatures. Do the hobbits perhaps descend from the Avari?

I noticed these issues aren't in the schedule of topics, so perhaps this thread is the correct place for talking about these matters.

|

|

|

Roverandom

Nevrast

Apr 17 2024, 7:12pm

Post #5 of 68

(12032 views)

Shortcut

|

To quote Sam Gamgee: "Well, I'm back." The many ups and downs of life have kept me off the boards for quite a while, but I'm going to make a concerted effort to get back in the game. Glad to have this opporunity to share some thoughts on the Shire! I'm not sure that I have any (Middle)Earth-shattering answers to your very good questions, but they have sparked a few ideas that I'd like to share.

Re: THE LAND

When Frodo asked Sam about his opinion of the Elves of Lorien, he replied, “I reckon there’s Elves and Elves. They’re all elvish enough, but they’re not all the same. Now these folk aren’t wanderers or homeless, and seem a bit nearer to the likes of us:they seem to belong here, more than even hobbits do in the Shire. Whether they’ve made the land, or the land’s made them, it’s hard to say, if you take my meaning.” I think that the beauty of Tolkien's world-building is that different peoples seem to have that same relationship to their chosen homes. Consider also the Breeland and the comment "Nowhere else in the world was this peculiar (but excellent) arrangement to be found.." Or the obvious relationships between the Rohirrim and the green fields of Rohan, the Dwarven kingdoms under various mountains, and the successful free trade zone of Mirkwood/Esgaroth/Erebor/Dale. I agree with your point that the land shaped the hobbits as much as they shaped it, and would argue that the same could be said in these other cases.

As a side thought, you mention the Dwarves in the Shire. I think that there is a whole separate discussion that could be made of the wandering travelers who have no time to stop for another group on the Great Road, the nameless Party helpers staying at Bag End, etc.

Re: THE PEOPLE

I think the Shire, and particularly the eponymous Hobbiton of which we are most familiar, is certainly meant to seem like Utopia at first glance. The fact that it is not, and that it is shown to have some serious flaws by story's end, just makes it feel like more of a real place. That's also what, in my opinion, makes for good writing. LotR would just be another fairy tale without the depth of character that is shown here and in many other places throughout the book. Having said that, the Shire would be a lovely place to settle in one's retirement!

As far as how the hobbits view history, it fits in with the rest of their make-up. Conservative, as was mentioned, and certainly set in their ways --- not the least bit interested in what they aren't interested. They remind me of Iowans in The Music Man:

"Oh, there's nothing halfway

About the Iowa way to treat you,

When we treat you

Which we may not do at all."

Anyone who is unfamiliar with the musical should check out the rest of Iowa Subborn's lyrics. The song could just as well have been written about hobbits.

For just as there has always been a Richard Webster, so too has there been a Black Scout of the North to greet him at the door on the threshold of the evening and to guard him through his darkest dreams.

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 17 2024, 7:23pm

Post #6 of 68

(12026 views)

Shortcut

|

|

" . . . not the least bit interested in what they aren't interested."

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

Yes, I think that's pretty much it. Great way to put it! I think it makes the exceptions so much more exceptional. And poignant. It wouldn't be nearly the story it is without this contrast.

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 18 2024, 1:50am

Post #7 of 68

(12005 views)

Shortcut

|

|

"Could the hobbits have evolved their culture anywhere else in Middle-earth?"

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

"Could we expect a similar Shire in Harad or Rhun, or in the middle of Gondor? Or did it lie at a unique wilderness juncture of protection by Elves, Rangers, and a Grey Wizard, enabling its people to prosper and indulge in pleasant pastimes?"

I apparently have a minority opinion on this, at least partly. Yes, I think the rich, protected farmland with a convenient river and apt climate are relevant. Although, as others have said, those conditions existed elsewhere as did earlier hobbits, the nature of the land its environment in combination with its situation at a 3-way "juncture of protection," along with Bombadil as something of a buffer, gave the area a unique sort of stability. There were other Hobbit colonies, but eventually they found it necessary to move, and, from what I understand, were not in an environment as stable and as protected long-term as was the case in the Shire.

I think all this taken together would encourage those tendencies of insularity and conservatism, which is natural, since the Hobbits had an environment there in the Shire which they had reason to want to preserve as-is.

So, I think all these rural English village characteristics Curious mentioned would have been entrenched and intensified in the Shire, which could easily give rise to it's own slant on basic Hobbit character, and probably some more specialized customs.

|

|

|

Hamfast Gamgee

Dor-Lomin

Apr 18 2024, 10:42am

Post #9 of 68

(11959 views)

Shortcut

|

Does there exist anywhere an official map of the Shire? I know there is one in Lotr but that is only part of the Shire. I'm not 100% clear where the borders really are. I also wonder if it is bigger than we might think. It certainly takes the Hobbits a few days to travel across it. By foot anyway,

|

|

|

GreenHillFox

Nevrast

Apr 18 2024, 2:08pm

Post #10 of 68

(11936 views)

Shortcut

|

|

About the borders of the Shire

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

In the Prologue one can find the following indications:

For it was in the one thousand six hundred and first year of the Third Age that the Fallohide brothers, Marcho and Blanco, set out from Bree; and having obtained permission from the high king at Fornost, they crossed the brown river Baranduin with a great following of Hobbits. They passed over the Bridge of Stonebows, that had been built in the days of the power of the North Kingdom, and they took all the land beyond to dwell in, between the river and the Far Downs.

This indicates the limits in the West (the Far Downs) and in the East (except that in the East the hobbits annexed Buckland later on, making the Old Forest a part of the East border too).

Nothing seems to have been mentioned about the borders North and South; but in the same Prologue we also have this:

Forty leagues it stretched from the Far Downs to the Brandywine Bridge, and fifty from the northern moors to the marshes in the south.

By the latter, I suppose the Overbourne Marshes are meant. One league is assumed to correspond to 3 miles or 4.8km.

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 19 2024, 1:53am

Post #11 of 68

(11876 views)

Shortcut

|

THE PEOPLE

While Tolkien mentions a few things hobbits don't like such as complex machinery, by and large he develops their culture by demonstrating what they enjoy.

Quote

they love peace and quiet and good tilled earth: a well-ordered and well-farmed countryside was their favourite haunt.

Not that it ends there. Birthdays were a perpetual delight.

Quote

Actually in Hobbiton and Bywater every day in the year was somebody’s birthday, so that every hobbit in those parts had a fair chance of at least one present at least once a week. But they never got tired of them.

And drinking and eating from noon to midnight was easily achievable regardless of age.

At other times there were merely lots of people eating and drinking – continuously from elevenses until six-thirty, when the fireworks started...About midnight carriages came for the important folk.

Does this sound like Rivendell or Minas Tirith to you? Can you readily imagine all-day community birthday parties and fireworks in those places? (rhetorical) What does it tell us about hobbit priorities in life?

Both Rivendell and Minas Tirith are more "serious" then the Shire-folk in general. But Rivendell, in a fairly protected environment, has much more of a relaxed social environment then Gondor, where, as thedescendants of Numenorians, everyone seems to either take themselves or at least their culture very seriously. And of course they are in the middle of a war so it's understandable that anything that might simply be thought of as "fun" or frivolous wouldn't be likely to occur.

So it seems to me that both Rivendell and the Shire have some social similarities partly because they are in a more protected environment, and also one where the struggle for daily existence isn't very difficult.

Except for those "tra-lallys" in The Hobbit, "Rivendellian" culture seems calm and dignified, but social gatherings are common and possibly hosted dinners may be as well, although we only have one instance in the Lord of the Rings due to all those distinguished visitors. The Hall of Fire gathering did seem to be a regular occurrence, with Bilbo bringing Shire culture right into the middle of it. They didn't always seem to take him seriously, but they seem to enjoy his presence in what seems like a relaxed atmosphere.

"'Now we had better have it again,' said an Elf. Bilbo got up and bowed. 'I am flattered, Lindir,' he said. 'But it would be too tiring to repeat it all.' 'Not too tiring for you,' the Elves answered laughing. 'You know you are never tired of reciting your own verses. But really we cannot answer your question at one hearing!' 'What!' cried Bilbo. 'You can't tell which parts were mine, and which were the Dunedain's?' 'It is not easy for us to tell the difference between two mortals,' said the Elf. 'Nonsense, Lindir,' snorted Bilbo. 'If you can't distinguish between a Man and a Hobbit, your judgement is poorer than I imagined. They're as different as peas and apples.' 'Maybe. To sheep other sheep no doubt appear different,' laughed Lindir. 'Or to shepherds. But Mortals have not been our study. We have other business.' 'I won't argues with you,' said Bilbo. 'I am sleepy after so much music and singing. I'll leave you to guess, if you want to.'"

I would say that social gatherings in Gondor seem nonexistent, other than simply gathering for lunch because they had to eat. And the obvious priority socially and otherwise would be discipline and a focus on whatever was necessary for the survival of the culture.

Rivendell's values, based only on the social gatherings we are told about, would seem to be calm, relatively dignified interactions in a pleasant atmosphere--with touches of humor; as well as a love of culture, poetry and song. I'm guessing that until Bilbo came along, that was generally what might be called "high culture," although we still have those tra-lallys in the Hobbit.

What the Hobbits in the Shire value socially as priorities--if you only think of the Unexpected Party and the lead up to it--are things like humor, jokes, generosity, a relatively egalitarian approach to each other compared to the other two cultures, with a relaxed approach to dignity and manners, like the Proudfeet on the table, which people did notice, but no one seem to feel the need to rebuke.

Mixed in with conviviality is the hobbit penchant for gossip, either in taverns or in homes like Farmer Maggot's:

‘Drownded?’ said several voices. They had heard this and other darker rumours before, of course; but hobbits have a passion for family history, and they were ready to hear it again.

Though curiously hobbits' love of gossip-history doesn't connect with a love of lore-history.

A love of learning (other than genealogical lore) was far from general among them,

Although a love of learning was far [away] from the state of being generally present among them, "general" does leave room for a fair number of individual exceptions.

Do hobbits make sense in a Middle-earth where history is usually revered by the wise and ignored by the foolish? What could explain hobbits' disinterest in history?

The Hobbit's interest in genealogy was about family identity and belonging, and social standing, and the reasons people our interested in places like ancestry.com, like a sense of pride and inspiration, and possibly a hope for continuity based on the status and accomplishment of their ancestors. It's not about history as such.

If the Shire is anything, it seems to be about who is who, and how they relate to each other, and just a general sense of belonging, although there is definitely some social stratification.

But it wouldn't be surprising if, for some, this digging into family history would spark an interest in history in general. I wonder if that's what got Bilbo interested.

|

|

|

Annael

Elvenhome

Apr 19 2024, 3:52pm

Post #12 of 68

(11817 views)

Shortcut

|

|

this has always been a favorite idea with me

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

that the land shapes the people and the culture. I picked that idea up from James Michener after reading The Source, where he posits that religions which came out of the desert tend to be harsher than religions that arose in other areas. But mostly I think about it in relation to colonization. Colonizers oppress indigenous people and cultures when they first arrive, but the longer they live on that new land, the more--I think and hope--the land itself works on them, until they start to become open to and even adopt some of the ways of the local natives. We call it cultural appropriation but perhaps it goes deeper than that. Here in the Pacific Northwest of the US, awareness of and interest in local tribal customs has been steadily growing, more and more people are using native names for local features, and the tribes are having more and more influence on state environmental practices. My feeling is that this is all because most people just can't live in this beautiful place for long without coming to love it and wanting to tend to it with respect. Even the hardest-hearted respond with rejoicing any time the clouds part and "the Mountain" - Rainier, or to use its original name, Tahoma - can be seen, and most of the people I know go so far as to say "that's my mountain." We feel a personal relationship.

I am a dreamer of words, of written words.

-- Gaston Bachelard

* * * * * * * * * *

NARF and member of Deplorable Cultus since 1967

(This post was edited by Annael on Apr 19 2024, 3:53pm)

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 19 2024, 6:43pm

Post #13 of 68

(11805 views)

Shortcut

|

Our spot has been RMNP, and it always feels like coming home. We always approach them by driving in the same way, because to us it's like a carefully written but divinely inspired symphony. First, there is the glimpse of the high peaks at the edge of the high plains, where we all try to figure out who has really seen them first, or are they "just clouds." Then it's the approach through Big Thomson Canyon, where my mom always sings part of Brahms first symphony, and the rest of us are mostly inspired to awed silence. And then the Rockies open out. I would say that land has shaped us profoundly, even though we don't live there, but perhaps the plains where we grew up shaped us into people who desire uplift and exaltation.

(There's something about the plains, too.)

Unfortunately, like the plains, some landscapes seem to inspire use rather than appreciation, although that, too, has begun to shift; but I agree that mountains and their surroundings are so intoxicating--and arresting--that it would be natural for that to begin to change people.

(This post was edited by Ethel Duath on Apr 19 2024, 6:44pm)

|

|

|

Curious

Gondolin

Apr 22 2024, 12:24am

Post #14 of 68

(11552 views)

Shortcut

|

|

The problem with assessing hobbit technology is we know it’s anachronistic.

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

If the hobbits have mantle clocks that keep accurate time that’s advanced technology compared to the rest of Middle Earth. But do they really have mantle clocks? It’s hard to say.

Similarly, the hobbits have morning and evening mail, and long and complicated wills, suggesting they are highly literate. But are they really highly literate, or is this another anachronism?

|

|

|

Curious

Gondolin

Apr 22 2024, 1:14am

Post #15 of 68

(11549 views)

Shortcut

|

|

Writer Guy Davenport claimed that Tolkien latched on to his classmate’s tales of Kentucky.

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

The classmate of Tolkien’s was Allen Barnett, a Kentucky lawyer. Davenport claimed Barnett had no knowledge of Tolkien’s fiction, but remembered how much he liked tales of Kentucky. Davenport quoted Barnett saying:

“‘You know, [Tolkien] used to have the most extraordinary interest in the people here in Kentucky. He could never get enough of my tales of Kentucky folk. He used to make me repeat family names like Barefoot and Boffin and Baggins and good country names like that.’”

Davenport noted that tobacco is grown and cured in Kentucky like pipeweed is in the Shire:

“Practically all the names of Tolkien's hobbits are listed in my Lexington phone book, and those that aren't can be found over in Shelbyville. Like as not, they grow and cure pipeweed for a living. Talk with them, and their turns of phrase are pure hobbit: ‘I hear tell,’ ‘right agin,’ ‘Mr. Frodo is his first and second cousin, once removed either way,’ ‘this very month as is.’ These are English locutions, of course, but ones that are heard oftener now in Kentucky than England.”

I have never seen any corroboration of Davenport’s claim, and it may just be that the rural village in which Tolkien grew up has a lot in common with rural villages in Kentucky or, as you suggest, Iowa. But the tobacco connection is interesting, and I don’t think they cured tobacco in Tolkien’s English village.

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/23/archives/hobbits-in-kentucky.html

(This post was edited by Curious on Apr 22 2024, 1:18am)

|

|

|

Otaku-sempai

Elvenhome

Apr 22 2024, 2:08am

Post #16 of 68

(11537 views)

Shortcut

|

If the hobbits have mantle clocks that keep accurate time that’s advanced technology compared to the rest of Middle Earth. But do they really have mantle clocks? It’s hard to say.

Similarly, the hobbits have morning and evening mail, and long and complicated wills, suggesting they are highly literate. But are they really highly literate, or is this another anachronism?

I still suspect that Bilbo's mantle clock was of dwarvish make. The technology needed seems more in-line with the Dwarves.

Tolkien writes in his prologue to LotR that some hobbits were literate, but it was hardly universal. Mostly, it seems that it was the more well-to-do families where literacy flourished.

“Hell hath no fury like that of the uninvolved.” - Tony Isabella

|

|

|

Ethel Duath

Gondolin

Apr 22 2024, 3:16am

Post #17 of 68

(11531 views)

Shortcut

|

and found some old phone book records from Lexington, and randomly checked 1972. https://babel.hathitrust.org/...89223314&seq=131

I didn't find actual Hobbit last names, but I did find Buffin, Berryhill, Berryman, Barrow, Barnhill, and best of all, Bagshaw (Bagshot Row?).

|

|

|

Silvered-glass

Nargothrond

Apr 22 2024, 12:09pm

Post #18 of 68

(11477 views)

Shortcut

|

|

The Formal Side of the Hobbits

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

It is easy to see the hobbits as more free-spirited than they really are.

Otho would have been Bilbo’s heir, but for the adoption of Frodo. He read the will carefully and snorted. It was, unfortunately, very clear and correct (according to the legal customs of hobbits, which demand among other things seven signatures of witnesses in red ink).

I wonder how many wills have been invalidated because of ink color. Otho could have ended up owning Bag End and the One Ring if Bilbo had made a small technical error in his will, and the entire plot would have been derailed.

"I do take Sméagol under my protection," said Frodo. Sam sighed audibly; and not at the courtesies, of which, as any hobbit would, he thoroughly approved. Indeed in the Shire such a matter would have required a great many more words and bows.

The hobbits also appear to have degrees in how low they bow, though the text doesn't make a big deal of it. A modern person visiting the Shire could get quite an East Asian impression.

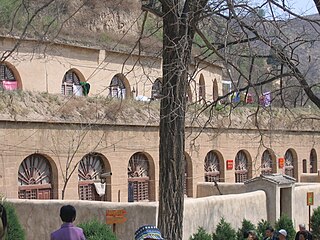

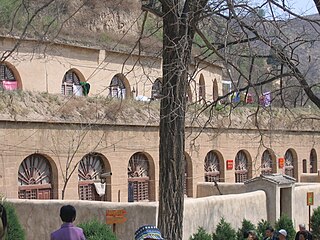

And speaking of East Asia, hobbit dwellings appear to be based on the Chinese yaodong. Perhaps in Tolkien's world the two have a shared origin in the mists of the history that the hobbits chose to forget.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaodong

This yaodong was used by Mao as his headquarters:

If the windows and doors were fully round instead of half round, the building would match Tolkien's descriptions. I wonder if "No admittance except on party business" was a subtle joke referencing this with a birthday party in place of a Communist party.

|

|

|

Silvered-glass

Nargothrond

Apr 22 2024, 3:55pm

Post #19 of 68

(11470 views)

Shortcut

|

|

The Plausibility of Hobbit Technology

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

The Shire is an unusually sheltered place in Middle-earth, which would give a chance for technology to flourish in an entirely plausible way. The Shire also is capitalist in its economic structure, allowing for rich hobbits to invest in new production methods and hire workers. There should be plenty to hire with the expanding population. As for hobbits supposedly not being interested in advanced technology, Lotho Sackville-Baggins and Ted Sandyman show otherwise. It only takes a few innovators in the right place to push technology forward.

Middle-earth has very large differences between cultures because people just don't get around very much. Gondor is more advanced in many ways than Rohan, and near the two live the hunter-gatherer Drúedain. The North despite its general wildness at least has some trade routes, which give the hobbits access to metals while Dwarves get to import agricultural products such as pipeweed. The Sackville-Bagginses are mentioned to own a plantation, so it's not all just cozy little family farms.

According to Wikipedia, the clock on Bilbo's mantelpiece would require early 15th century technology at the minimum, which sounds hardly impossible:

Minor developments were added, such as the invention of the mainspring in the early 15th century, which allowed small clocks to be built for the first time. https://en.wikipedia.org/..._timekeeping_devices

It is unclear if Bilbo's clock was advanced enough to have a pendulum, but there is nothing in the text requiring for the Shire clocks to have the refinements to make them truly accurate. Bilbo's clock could well be off by multiple minutes each day, the actual amount varying with the weather. Hobbits in any case do clearly have some capability to work with gears, as can be seen in the existence of the watermill, an an ancient invention but nevertheless possessing a degree of mechanical complexity. The application of waterpower in industry beyond grinding grain also dates to classical antiquity.

Notably according to Wikipedia, the first attested paper mill in Europe dates to 1282. Paper is shown as common and affordable in the Shire. A few competing paper mills explains this handily.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watermill

The curved mirror that Bilbo gifts to Angelica Baggins also shows that optics are not unknown in the Shire nor good mirrors prohibitively expensive. Speculatively speaking, it would not be impossible for a clever hobbit to develop a telescope. It is only a small cognitive step from seeing one's face looking big to wanting to see distant objects looking big. We know that hobbits such as Frodo do look at the sky and care about the names of the stars and the constellations, so a curious hobbit looking through a primitive telescope and discovering the moons of Jupiter would be entirely plausible.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 23 2024, 3:23am

Post #20 of 68

(11430 views)

Shortcut

|

In general, I thought Tolkien was not an admirer of the USA, but people can always make exceptions, and maybe he liked smoking tobacco so much, he felt a special spot in his pipe for Kentucky and its ways. It's clear in LOTR that pipeweed/tobacco is special not just for the pastime it supports but for hobbit pride. Just think of Merry meeting King Theoden for the first time and launching into the story of Old Toby finding the first pipeweed, as if everyone should know that story.

It is the cultural diversity of M-Earth that makes it so interesting, even if some seems transparent, such as Oxfordshire = Shire, Norse/Germanics = Rohan, or rustic tribes found in the Amazon or Papua New Guinea = Ghan Buri Ghan's people. It still works. I think like for any good chef, he was a master at mixing the ingredients into a great new culinary delight.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 23 2024, 3:42am

Post #21 of 68

(11436 views)

Shortcut

|

|

Good point about the Druadan, but

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

I think something essential to the Shire is how gentle and easily prosperous the people are, and that's a reflection of the protection they receive from the Rangers as well as their distance from any harmful realm. It's just a thought experiment and has no definitive answers, and I think on a purely speculative basis that the Shire might exist where the Woodmen of Mirkwood live. We know next to nothing about them, but they seem to be a small realm with their own rules like the Shire, and they don't get wiped out by forces from Dol Guldur or invaders from Rhun, as if they live below the radar as the Shire-hobbits do.

And while the Shire may seem idyllic, the hobbits themselves can be petty, gossipy, and irritating. Note that Bilbo has no close friends his own age. He must make do with Frodo and Frodo's friends. A zillion years ago when Barliman's Chat was active on this site and I participated in book talks there, I remember someone named Christine giving a memorable distinction between romanticized and idealized societies: "in romanticized ones the garbage never stinks. In ideal ones, there is no garbage." So that helps me keep perspective on the lovable Shire: it's romanticized, but it still has garbage like gossip, envy, and regional bigotry. But I'm not a cancel culture guy, so I still think it's a great place, and I'd happily live in Bag End, but I'd turn my nose up at the dirt holes on Bagshot Row along with the suspicion of literacy.

Good point about Bilbo/Frodo lacking friends. That bothered me since my very first read. Usually the heroes of quests are rewarded with gold, fame, pretty wives, and lots of friends, and that reader bias lingers, making me rueful that they are lonely bachelors. And it's a bit odd that Tolkien wrote that fate for both of them, but I think he saw it as a natural product of Shire cultural conformity where eccentric, rich heroes just don't fit in.

And thanks for yet another dose of CuriousTM insight, which is why it's so nice to see you here again:

Q. Why does Shire culture produce quest heroes like Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin?

A. It normally doesn't. These are exceptional hobbits. And they are the direct result of Gandalf's meddling. He deliberately infected Bilbo with the wandering bug, and interest in elvish, and all kinds of strange notions and knowledge, and it just took a while for it to spread to another generation of young hobbits.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 23 2024, 3:55am

Post #22 of 68

(11433 views)

Shortcut

|

And thanks for your input, including enlarging on my point about people belonging to their land and vice versa:

Consider also the Breeland and the comment "Nowhere else in the world was this peculiar (but excellent) arrangement to be found.." Or the obvious relationships between the Rohirrim and the green fields of Rohan, the Dwarven kingdoms under various mountains, and the successful free trade zone of Mirkwood/Esgaroth/Erebor/Dale. I agree with your point that the land shaped the hobbits as much as they shaped it, and would argue that the same could be said in these other cases.

When I do re-reads of any part of LOTR, it always feels like there's a sort of hazy mingling zone between a land and its people, similar to ocean rocky beaches where the mist mingles with the air and forms a combination of the two. It gives readers the feeling that people belong where they are and it's a crime against nature to dislodge them, which helps involve us in the struggles of the good guys. Isn't it a crime for ruffians to disrupt the Shire's comfort and laxity about rules, or for Saruman and Sauron to put pressure on the happy horses of Rohan? Just feels wrong, like seeing a helpless person beat up in the street that makes your blood boil, so you get involved on the right side. That observation that Sam makes packs a lot of philosophical punch.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 23 2024, 4:03am

Post #23 of 68

(11432 views)

Shortcut

|

|

You're not alone. I think the Shire is a Silmaril of sorts

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

A one-of-a-kind creation not to be reproduced anywhere else, just as Breeland was unique.

The Prologue, "Concerning Hobbits," has this to say, which makes me think it was part fate, part hobbit-will that forged the Shire-hobbit connection after they migrated there from Breeland:

At once the western Hobbits fell in love with their new land, and they remained there,

That instant love, like falling in love at first sight, which is how Elves fall in love. I think it was meant to be.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 23 2024, 9:53pm

Post #24 of 68

(11371 views)

Shortcut

|

And here we have one answer to many of my scattered questions:

If the Shire is anything, it seems to be about who is who, and how they relate to each other, and just a general sense of belonging, although there is definitely some social stratification.

I appreciate your explanation of their interest in genealogy, which to me is history, but I think you're much more on target with:

The Hobbit's interest in genealogy was about family identity and belonging, and social standing, and the reasons people are interested in places like ancestry.com, like a sense of pride and inspiration, and possibly a hope for continuity based on the status and accomplishment of their ancestors.

Now I get it. A Baggins would study 20 generations of Baggins to feel good about being a Baggins in the present, have bragging rights about past Bagginses, and continue a sense of social status and entitlement. (Not the same historical curiosity I abound with, such as how did the relatively small population of medieval Vikings get all the way to modern-day Ukraine!?!?!?!?!?)

Then re: your comments on Rivendell and Gondor: I think we're helped to understand Rivendell culture because not much happens there, so Tolkien is at his leisure to describe the place. By contrast, it's always something that I feel is a bit missing in Gondor: what is the culture of this place when it's not at war? We are given hints and asides, but I guess I always want more.

|

|

|

CuriousG

Gondolin

Apr 24 2024, 5:54pm

Post #25 of 68

(11285 views)

Shortcut

|

|

I think people always adapt to the land more than they realize themselves

[In reply to]

|

Can't Post

|

|

And as an American, it's always baffled me a bit in our history that even though the European colonizers felt superior to the Native Americans when they took their land, look at how many Native names were retained for states, cities, rivers, etc., rather than replacing all those names with "better" names of Euro-origin.

In the Shire's case, I feel like the land could have lain fallow for centuries and that would have been okay, but it had a sort of agency, I believe, and embraced the hobbits' presence when they arrived, just as they embraced it as their home in a symbiotic relationship. That does seem rather nebulous and New Age-y, but it's still a gut feeling I have whenever reading about Shire-hobbits.

|

|

|

|

|