News from Bree

spymaster@theonering.net

Jun 15 2014, 2:57am

Post #1 of 1

(393 views)

Shortcut

|

|

Tolkien and the virtues of fairy-stories

|

Can't Post

|

|

In our latest Library piece, TORn feature writer Tedoras discusses 10 key excerpts from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous lecture On Fairy Stories. In our latest Library piece, TORn feature writer Tedoras discusses 10 key excerpts from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous lecture On Fairy Stories.

In case you've never read it, On Fairy Stories (which Tolkien first delivered as a lecture in 1939) examines the fairy-story as a literary form, and explains Tolkien's philosophy of what fantasy is, and how it ought to work. As Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson write in their introduction to the expanded 2008 reprint, On Fairy Stories is "[Tolkien's] most explicit analysis of his own art".

The virtues of fairy-stories

By Tedoras

Professor Tolkien--as he was known then--was a very busy man in 1938. Not only was he beginning to develop what would become The Lord of the Rings, but he also delivered at this time one of his most famous lectures, titled "On Fairy-stories."

The original lecture was given as an Andrew Lang lecture at the University of St. Andrews; later, in 1947, it would be enlarged and published in Essays presented to Charles Williams by Oxford University Press. Today, "On Fairy-stories" can be found most readily in Tree and Leaf (or The Tolkien Reader, which contains the former).

This fine piece of scholarship provides a complete examination of fairy-stories, their origins, virtues, and historical context. In many ways, however, it is more concerned with the nature of Faėrie itself, especially from the perspective of the sub-creator (this notion first appearing in the lecture) and the reader.

The text offers much to fans of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, though few ever chance to stumble upon it. Below, I highlight some passages exemplary of the prolific wisdom and scholarship on display in this work, with the hope that it may lead some Tolkienites to discover (or rediscover) this wonderful and insightful (not to mention thoroughly amusing) read.

Passage #1

Most good "fairy-stories" are about the adventures of men in the Perilous Realm or upon its shadowy marches. Naturally so; for if elves are true, and really exist independently of our tales about them, then this also is certainly true: elves are not primarily concerned with us, nor we with them. (38)

Tolkien, true to his own words here, provides a similar setup in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings: one in which someone familiar and relatable is thrown into something wholly unknown. This hallmark of the successful fairy-story highlights Tolkien's own artistic ability; for certainly hobbits are not men, but he is able to paint such a vivid, lifelike portrait of those creatures that even readers--that is, those outside the sub-creator's mind--can begin to understand them.

It is also remarkable that we should find here what is largely taken for granted in Middle-earth: the nature of elves and their relationship to us.

Passage #2

Faėrie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible. It has many ingredients, but analysis will not necessarily discover the secret of the whole. (39)

As Tolkien fans, and some of the most "obsessed" (if that is the right word) fans in general, the question is often put to us why: why do you love these works so much? It has always been difficult for me to answer this question--for how can I describe thousands of pages of magic in a few sentences?

It seems the Professor himself was aware of this quality of fairy-stories, one that is wrapped up in wonder and mystery and desire; and a quality that can never been fully understood until internalized through immersing oneself in the text imagined for just such a purpose. This point on analysis in the last sentence will also be important later.

Passage #3

In Dasent's words I would say: "We must be satisfied with the soup that is set before us, and not desire to see the bones of the ox out of which it has been boiled..." By "the soup" I mean the story as it is served up by its author or teller, and by "the bones" its sources or material--even when (by rare luck) those can be with certainty discovered. But I do not, of course, forbid criticism of the soup as soup. (47)

Who knew so much rarefied academic talk on the origins of contemporary literature could be boiled down (forgive the pun) to a mere conversation about soup? Interestingly, this snippet fits oddly well into an argument Tolkien fans and academics alike know too well: that of allegory versus application. Here, the Professor himself proclaims his preference for looking at a work as itself, not the sum of its inspirations or sources. Who knew so much rarefied academic talk on the origins of contemporary literature could be boiled down (forgive the pun) to a mere conversation about soup? Interestingly, this snippet fits oddly well into an argument Tolkien fans and academics alike know too well: that of allegory versus application. Here, the Professor himself proclaims his preference for looking at a work as itself, not the sum of its inspirations or sources.

He goes on to call the question of origins the "least important...for my purpose;" an undoubtedly resounding disregard. And throughout the lecture, he takes up this mantle again; it is almost an obsession of his to fight off contemporary regard for the veritable "bones" of a work--but it is quite interesting how this fits into the context of Tolkien's own works, which may be some of the most complex and convoluted "soups,"¯ in terms of their "bones," that there are.

Passage #4

In describing a fairy-story which they think adults might possibly read for their own entertainment, reviewers frequently indulge in such waggeries as: "this book is for children from the ages of six to sixty."¯ But I have never yet seen the puff of a new motor-model that began thus: "this toy will amuse infants from seventeen to seventy"¯; though that to my mind would be much more appropriate. Is there any essential connexion between children and fairy-stories? Is there any call for comment, if an adult reads them for himself? Reads them as tales, that is, not studies them as curios. Adults are allowed to collect and study anything, even old theatre programmes or paper bags." (57-8)

We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien's ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children. We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien's ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children.

He himself resents the notion; his interest in fairy-stories was not truly piqued until he reached university, he later says. The tone with which he addresses these questions does not dissipate throughout the text; indeed, the questions themselves pop up here and there, and they lead to a discussion not only of the virtues and values of fairy-stories, but even unto one of psychological and sociological proportions.

Passage #5

[Literary belief] has been called "willing suspension of disbelief."¯ But this does not seem to me a good description of what happens. What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful "sub-creator." He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is "true": it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside."¯ (60)

To Tolkien, the successful creation of this Secondary World in literature is the highest art, if not the very "magic" itself. Suspension of disbelief results from a failure on the story-maker's part, as it thus requires a conscious effort on the part of the reader (and this, being conscious, removes the reader from the Secondary World); acceptance of the Secondary World, or the acceptance of verisimilitude, is what the author hopes to achieve in his audience.

Tolkien says that disbelief is that to which we "descend"¯ when we return to the Primary World and from there look unto the Secondary, instead of immersing ourselves in the latter. His words are harsh here, indeed; but only because immersion in the Secondary World, total immersion, is, as his tomes do attest, perhaps the Professor's greatest craft and the very reason we choose to read fairy-stories. We experience exactly what he says we should; while in Middle-earth, we are, in fact, in another world, fully accepting of its truths.

It is only when we retire to the Primary World that we reduce this work of art to a scientific endeavor, render it for analysis and scrutiny beyond its verisimilitude. While we are immersed, all that matters is the (literary) present.

Passage #6

Fairy-stories were plainly not primarily concerned with possibility, but with desirability. If they awakened desire, satisfying it while often whetting it unbearably, they succeeded. (63)

Here, the Professor is concerned with issue of belief, specifically on the part of children, in the context of fairy-stories. Children, he notes, are interested in the truth of fairy-stories as similar or different from their world. He posits the theory that belief is not wished for; that, as he says, though he "desired dragons with a profound desire," he "did not wish to have them in the neighbourhood, intruding into [his] relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear" (64).

The desire, the window into a tempting "Other-world" of wonder in both beauty and fear that Fantasy provides, that is what's important. This is but a fragment of a much larger section dealing mostly with the works of famous children's book author Andrew Lang, which Tolkien analyzes both from his childhood perspective and that of his present adulthood; it is quite an interesting bit of scholarship for Tolkienites, since many of us, like the Professor, grew up with a love of Fantasy that has changed and matured as we have.

Passage #7

The process of growing older is not necessarily allied to growing wickeder, though the two do often happen together. Children are meant to grow up, and not to become Peter Pans. Not to lose innocence and wonder, but to proceed on the appointed journey...But it is one of the lessons of fairy-stories (if we can speak of the lessons of things that do not lecture) that on callow, lumpish, and selfish youth peril, sorrow, and the shadow of death can bestow dignity, and even sometimes wisdom. (66-7)

I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the "allegory-application" debate) is clearly evident. I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the "allegory-application" debate) is clearly evident.

I find this inherent contradiction in Faėrie to be one of Tolkien's prime occupations throughout the work; Faėrie, if nothing else, is full of dichotomies: it is both beautiful and dangerous, it is for pleasure and for learning, it is for children and adults. Yet where does the Professor ultimately settle on these issues?

Passage #8

We should look at green again, and be startled anew (but not blinded) by blue and yellow and red. We should meet the centaur and the dragon, and then perhaps suddenly behold, like the ancient shepherds, sheep, and dogs, and horses--and wolves. This recovery fairy-stories help us to make. In that sense only a taste for them may make us, or keep us, childish. (77)

The Professor is here speaking of recovery, which he calls the "regaining of a clear view,"¯ a virtue of fairy-stories that he likens to cleaning windows in order to remove "triteness or familiarity" (77). In the closing of the essay, beginning in this section, we see more of Tolkien as the naturalist he was. The Professor is here speaking of recovery, which he calls the "regaining of a clear view,"¯ a virtue of fairy-stories that he likens to cleaning windows in order to remove "triteness or familiarity" (77). In the closing of the essay, beginning in this section, we see more of Tolkien as the naturalist he was.

Here, he notes the simple and fundamental nature of fairy-stories; a characteristic which allowed him to recognize again "the wonder of...stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine" (78). This is the essence of the recovery provided by fairy-stories, grand and tall tales though they may seem to be: they allow us to return to our world, the Primary World, and to experience it through a clean "window."

All that we see after we put down the book and look up is new and refreshing and worthy of more attention and wonder that it seemed to be before. How many times have we ventured to Rivendell or Lorien only to return to our lives and seek out forests and rivers of our own?

Passage #9

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which "Escape" is now so often used...In what the misuser are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. (79)

Certainly, we would all agree with the Professor's remarks on Escape; it is undoubtedly one of the reasons we love retreating to Faėrie. As opposed to "product(s) of the Robot Age," the content of fairy-stories deals with more "fundamental things," such as natural phenomena (80).

In fact, "escapist"¯ though fairy-stories may seem, the Professor claims they are more "real" for dealing with natural things (like clouds and horses and elms) than those inclined to meddle with trains and cars and the spawn of the "Robot Age,"¯ as he calls it (81).

Tolkien firmly rejects the notion that the "real" world is motorized, mechanized, and industrialized, while a window to a distant, pastoral scene of knighthood and valor may somehow be less "real" if not entirely "fake." One was here before the other and though out of sight, it is not out of mind.

Passage #10

The Gospel contains a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels--peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: "mythical"¯ in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation...There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many sceptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. (88-9)

I must confess: I was utterly shocked when I turned to the Epilogue of the essay, whence this section is derived, and read what the Professor had to say in closing. Perhaps I was more surprised. For, here--amongst many great thoughts in the Epilogue, all of which convenience would not afford me to convey--the Professor applies his theory of fairy-stories to religion, to Christianity, and to the Bible, in particular.

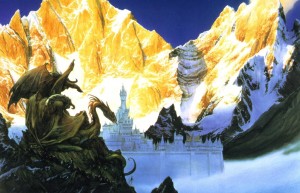

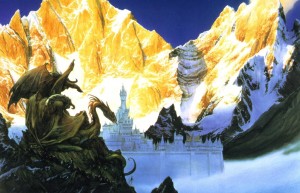

Vingilot leaving The Doors of Night by John Howe.

Here is the culmination, the ultimate culmination, of all the proper and necessary conditions for Faėrie--even man's desire for truth is bound up in it. But, more importantly, it ends in joy, as all fairy-stories must (that is the "eucatastrophe," a word which he coins in these final pages). Eucatastrophe is paramount in fairy-story resolutions and dénouement" and, certainly, the biblical example fits this paradigm quite well.

He calls his foray into this debate a "serious and dangerous matter"¯ and maybe even "presumptuous,"¯ but I believe some of the Professor's greatest work is to be found in the Epilogue to this essay--though, oddly, "On Fairy-stories" is often overlooked by Tolkien fans and scholars, but, when discovered, the Epilogue is, following the paradox, somehow ignored still.

I have here but given you but a glimpse of the magic in phrase-turning and academic stimulation that Tolkien lays out in "On Fairy-stories." I know I did not give everything away (much as I wanted to), and I hopefully whetted your palates with delight and desire, as is only fitting in a discussion of fairy-stories and fantasy. There is a wealth of knowledge left in this work to be discovered and enjoyed by Tolkien fans. How lucky, if not spoiled, are we as fans of an author who was himself a leading scholar in the genre of literature he pursued; Tolkien left for us the perfect guiding light to his texts, a roadmap of development and design in fairytale-making.

Whether you are seeking to gain insight into Tolkien's sub-creation, are perhaps interested in sub-creating on your own, or are in for a more philosophical and philological approach to fairy-stories, there is something in this essay of worth to you. Even those interested in Tolkien and religion will have much to peruse in the Epilogue; perhaps we should not be so hasty in labeling C.S. Lewis the religious theorist of the Inklings.

It will, doubtless, leave you with a different view of the man; one that is more academic and scholarly in nature, yet with equal (and unrivaled) wit and wisdom. Certainly, there is much we can still learn about Tolkien from this work, though tome after tome has yet been written about his life. Much has been overlooked; and I look forward to hearing what you discover.

References to the text are from the Del Rey Books edition of The Tolkien Reader, Random House Publishing Group, 1966.

Tedoras is a bibliophile, linguist, and regular attendee at TORn's live weekly webcast. He splits his time between scouring the web for Tolkien books to add to his collection and the study of Chinese politics and public policy.

(This post was edited by Silverlode on Jun 15 2014, 10:08am)

|

In our latest Library piece, TORn feature writer Tedoras discusses 10 key excerpts from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous lecture On Fairy Stories.

In our latest Library piece, TORn feature writer Tedoras discusses 10 key excerpts from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous lecture On Fairy Stories.  Who knew so much rarefied academic talk on the origins of contemporary literature could be boiled down (forgive the pun) to a mere conversation about soup? Interestingly, this snippet fits oddly well into an argument Tolkien fans and academics alike know too well: that of allegory versus application. Here, the Professor himself proclaims his preference for looking at a work as itself, not the sum of its inspirations or sources.

Who knew so much rarefied academic talk on the origins of contemporary literature could be boiled down (forgive the pun) to a mere conversation about soup? Interestingly, this snippet fits oddly well into an argument Tolkien fans and academics alike know too well: that of allegory versus application. Here, the Professor himself proclaims his preference for looking at a work as itself, not the sum of its inspirations or sources.  We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien's ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children.

We are come now to one of the most significant questions (or issues) surrounding fairy-stories: who is the audience for such works? Just as this question posed challenges to Tolkien, it remains unresolved in the literary world to this day. Yet here we glimpse a bit of Tolkien's ire, if not so artfully disguised in lexical nuance, at the notion that these stories exist only for, and perhaps because of, children.  I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the "allegory-application" debate) is clearly evident.

I find this quotation particularly magical and entertaining; it is undoubtedly a beautiful, yet underused bit of wisdom itself. The veritable juxtaposition of an almost innocent tone and such real understanding and wisdom is at once amusing and insightful. Tolkien, in a nearly reluctant way, outlines the essence of the virtue of fairy-stories; yet his hesitancy to attribute outside meaning (returning to the "allegory-application" debate) is clearly evident.  The Professor is here speaking of recovery, which he calls the "regaining of a clear view,"¯ a virtue of fairy-stories that he likens to cleaning windows in order to remove "triteness or familiarity" (77). In the closing of the essay, beginning in this section, we see more of Tolkien as the naturalist he was.

The Professor is here speaking of recovery, which he calls the "regaining of a clear view,"¯ a virtue of fairy-stories that he likens to cleaning windows in order to remove "triteness or familiarity" (77). In the closing of the essay, beginning in this section, we see more of Tolkien as the naturalist he was.